A vast majority of development projects in higher education focus on building infrastructure and jobs. And since the creation of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) in 2002 there have been thousands of them. So much so, that it is now argued that the focus on job creation has become the primary output of the HEC and not a by-product of organising a better education system.

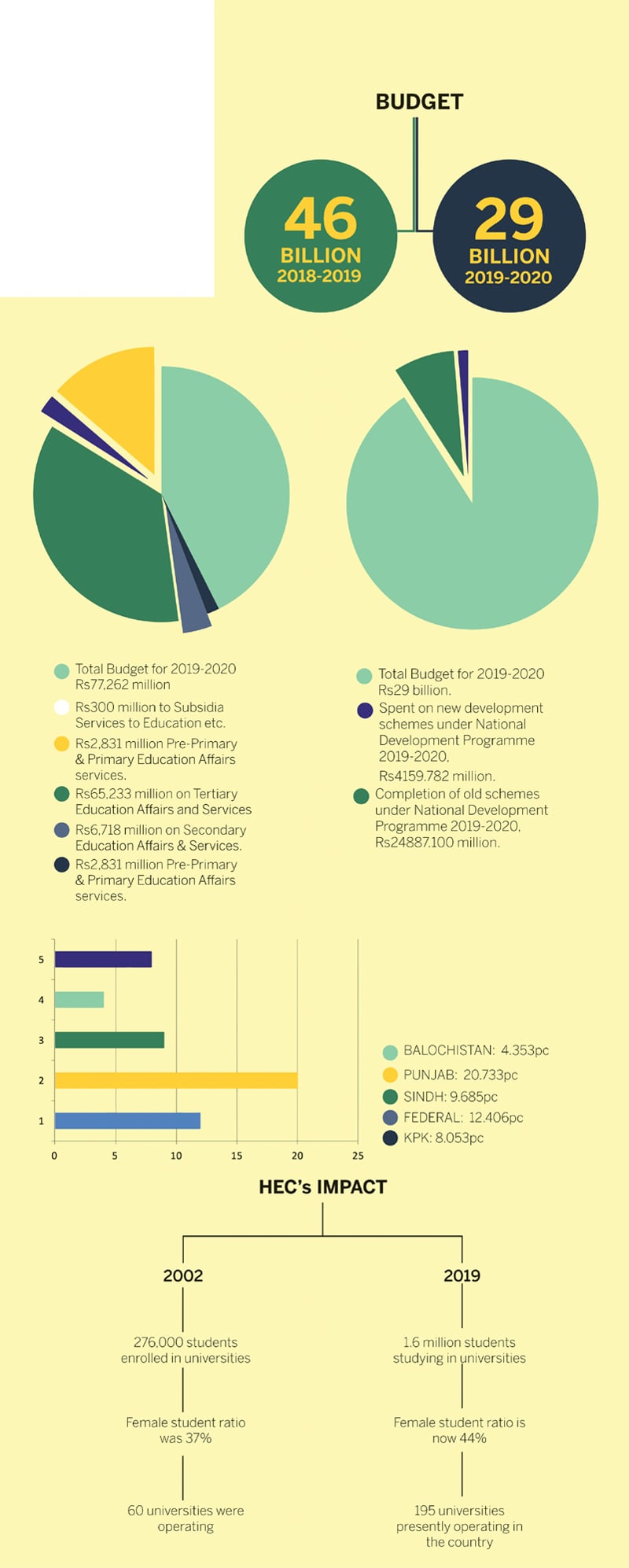

Yet the HEC has been cited as a prime example of how reform of moribund and unproductive ministries should be undertaken in Pakistan. In the first five years of its existence (2002-2007), the HEC brought about a major increase in the funds invested in universities across the country. During this first half decade, the HEC touted that it had overseen a purported increase of 5,000 percent in the budget allocated to the higher education sector. This was hailed unequivocally as a great success.

When the funds-starved higher education sector began to receive much needed inflow of cash, things certainly appeared to look better. Universities repaired their long dilapidated infrastructure. They sent their faculty to pursue PhDs abroad. They invested in scientific equipment and labs. They were able to increase enrolment to make tertiary education accessible to more people.

Read: HEC — stormy times up ahead

But with these improvements and accomplishments came many burdens. There was more money than there were ideas. Our academic institutions became flush with cash, relatively speaking, but it was far more cash than they had the capacity to spend intelligently.

Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission has had a roller-coaster history but part of the problems of higher education have to do with the government throwing money at problems rather than strategising and making smart investments. As much-needed reforms began to be undertaken, however, a former Planning Commission member warns that an effort is underway to revert back to old and wasteful ways of doing things

In hindsight, it is now visible that the pumping of money in the higher education sector was not such an unqualified success after all.

FLUSH WITH MONEY

Throwing money at a problem is hardly ever the solution, particularly for complex societal puzzles. In fact it is, more often than not, part of the problem itself.

Money can be a solution in relatively simpler scenarios where solutions scale linearly, such as retiring public debt, or where the underlying intervention is well-established and its scale is straightforward, such as building more schools leads to enrolling more out-of-school children into schools. But even here, rather than blindly throwing money at the problem as a quick fix, one must carefully watch out for the perils of saturation, of the impact on quality of outcomes, and of the ability (or lack thereof) of absorbing money.

For more complex problems, such as how to make Pakistan’s higher education system more productive, impactful and globally competitive, or how to reform our public science and technology infrastructure so that it starts delivering results, fund allocations should be carefully planned. Yet, blindly throwing money to solve a problem has often been the first resort and primary modus operandi of some policymakers.

In the initial years of its existence, when large amounts of money was pumped into the HEC, perhaps the most important of unintended consequences was the over-commercialisation of higher education in Pakistan. Public and private universities alike became profitable ‘ventures’ where billions of contracts and jobs had to be awarded.

As universities became a big real estate business, a significant portion of the university heads’ time began to be consumed in managing this sprawling estate — more degrees, more departments and more campuses around the country meant more real estate development and management. Oftentimes, this led to perverse effects. The offices of many professors, deans and vice chancellors at Pakistani universities expanded to become much bigger than the offices of their counterparts at European or American universities.

Many vice chancellors became more preoccupied in planning how to get the next billion-rupee public project or increase enrolment and, sometimes, improve their ‘rankings’ and worried less about whether their university had the capacity to produce quality, job-ready graduates. They spent more time thinking about how many faculty members they can send for PhDs abroad and less time thinking about the calibre of these faculty members and the quality of the institutes where they are sent.

Then, as the financial ‘incentives’ began to affect the decisions taken by the faculty, the higher education system entered a whole new race of ‘quantity vs quality’ in the production of post-doctoral graduates and the publishing of papers. There have even been allegations about faculty putting their colleagues’ names on their papers so as to increase their publication numbers. Universities do not distinguish between a paper published in a third-rate journal from one published in a highly selective and prestigious one. Our universities thus became paper mills producing a lot of, if not mostly, junk published in below-standard journals, many of which were later discovered to be fake.

Even today, our higher education system only counts the number of papers published as a way of quantifying its success and does bother to track citations or the true impact of the research. If you were to ask whether a Pakistani author features as a lead author for one of the top 1,000 most cited papers in the world, you would hardly find any. An attempt to identify any piece of research originating from a Pakistani university that left a substantial impact on global society, is a seriously frustrating task.

While there are always some good exceptions, a significant majority of the higher education system refelcts this mindset of prefering quantity over quality.

It has taken well over a decade for the higher education system to realise that money alone cannot solve problems — certainly not the kind of complex problems plaguing our higher education sector and even more complex societal problems such as climate change, basic illiteracy, water scarcity, etc.

SHRINKING OF FUNDS

The contraction of the HEC’s budget from 2008-2012 came as a blessing in disguise — although for the wrong (political) reasons. As money evaporated, only those who did research and published for the love of creating and disseminating knowledge continued to do so. University heads were also forced to check their wasteful ways and began to think frugally and make smarter choices.

The echelons of power in the government called for a second phase of reforms for the HEC that focused on building upon its achievements and critically evaluating what had gone wrong. However, this required a somewhat dispassionate view towards the first phase of HEC reforms (2002-2007) to really put everything under the lens of the evidence driving HEC policy.

An exercise to develop a Higher Education Vision 2025 to clearly define meaningful and impactful success metrics and create an oversight mechanism to keep the HEC (and universities) transparent was undertaken but it failed to take root. ‘Give us the money but don’t ask any questions’ was the attitude of the HEC’s old guard. For most of the projects, the HEC prided itself for its efficiency of spending money. Nobody seemed to care if this money was put to good use. For instance, an assessment of the HEC’s PhD programme resulted in one finding: All the money had been spent and the number of PhD scholarships awarded exceeded the target by a couple. There was no mention of the quality of PhDs produced, their absorption within the country, and their impact on national research. Project after project, the only accomplishment seemed to be that the money allocated to the HEC was being fully spent.

After ingesting five years of overdose and the subsequent contraction, the HEC first showed signs of withdrawal and then gradual recovery.

However, many felt that the pendulum had swung too much far in the other direction.

As the financial ‘incentives’ began to affect the decisions taken by the faculty, the higher education system entered a whole new race of ‘quantity vs quality’ in the production of post-doctoral graduates and the publishing of papers.

THE PLANNING COMMISSION

In the last five years, an effort was made to ‘revive’ the higher education sector through a gradual but significant increase in budgetary allocations, ideally linked with a new strategic plan for the HEC. It was felt that higher education cannot continue with the ‘low funding’ of the preceding five years, and neither can it afford to return to the unbridled and unaccountable ‘money rush’ experienced in its first five years.

This is where the Planning Commission came into the picture. The Planning Commission is where these disparate domains come together. The Planning Commission not only approves projects based on their individual merit but also looks at the broader national context and completing interests of various sectors.

While the Planning Commission did not have any remit to shape HEC policy, it had significant control over the development funding which constituted 20-25 percent of the HEC’s annual budget. And that’s the area where we began to introduce the new ideas of performance, accountability (not necessarily the financial kind) and impact. We believed the effectiveness of spending in the higher education sector could be increased manifold if it was tightly tied to real outcomes and impact, not merely input (money spent) or output (papers published or PhDs produced).

As this approach was diametrically opposed to the idea that money will solve everything, the Planning Commission was up against a culture — including an academic culture — devoid of performance, accountability, quality and impact. This was a direct outcome of the culture of fiscal irresponsibility that the HEC was saddled with at the start.

The Planning Commission rewrote the terms of reference of the HEC’s PhD and post-doctoral programme for the next eight years to make them performance-oriented and more accountable and established national centres in artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, data and cloud and cybersecurity, aimed clearly at solving national problems. Over five billion rupees were invested in high-quality faculty (as well as research associates, and PhD students) and equipment, but not a single penny was spent on buildings or physical infrastructure. We introduced (against stiff opposition from universities) the idea of sharing of equipment and data between universities and researchers; gradually began to re-introduce the age-old practice of international peer review as a way of assessing academic quality and performance; and funded a 21st Century Global Skills Initiative to create 100,000 certified professionals in highly demanded skills. We demanded that academics work harder to solve local problems and create local impact rather than work on global problems that get them published and left no impact on the country. All this is a matter of official record now.

This agenda of reform was initially seen with scepticism but as universities and faculty began to embrace it, a different tone was set within the higher education system. The HEC seemed to have turned a corner.

HEC IN TRANSITION

Through its journey, the HEC has responded to the crises of the times admirably. The initial funding, the subsequent squeeze, and the ensuing expansion did not hinder the HEC from meeting its targets, albeit with some questions about the quality and impact of those outputs. There may have been a time when money seemed to do the trick in overcoming the initial inertia and getting a cash-strapped system running. Not any more.

Today, the system must demonstrate that it can produce quality outcomes and the recent reforms have positioned it well to do just that.

Read: New HEC chair lays out vision for improvement in higher education

The current chairman of the HEC, Tariq Banuri, faces the unenviable task of taking these reforms forward by bringing together a coalition of partners, many of whom still long for the good old days of unbridled funds and no questions asked. Banuri faces formidable challenges from the old guard of the Musharraf era who want to go back to the past ways of doing things rather than embrace the ideas of performance, quality, accountability and impact. With his heart in the right place, he has admirably kept his focus on the strategy.

But a lot remains to be done. Unfortunately, the incumbent HEC set-up faces grave threats and danger from the proponents of the old ways of doing things.

It is now plain knowledge that an effort has been underway to undermine HEC reforms and revert to the old and wasteful ways of doing things. An effort to seek approvals for tens of hastily prepared projects was momentarily blocked by the bureaucracy but still continues to find support from the government. A large number of people (as many as 100 or more) were pushed to submit projects at a few days’ notice. Everyone who is someone, or no-one, in science and technology or higher education seems to be writing a PC1 document (Planning Commission Form 1 or PC1 is a project document) to be submitted to the Planning Commission for approval.

An unprecedented blanket approval seems to have been granted for billions of rupees of development funds to be squandered on hastily put together, ill-designed and ill-conceived PC1s written by amateurs, at best, and private interests at worst, who are enticed by the promise of billions in overnight funding approvals. Rs 30 billion, to be precise, in year one, with potential fall forward of over 150 billion rupees. And this is just the start. It seems like we’re in the summer of 2002 and it’s raining greenbacks.

The only problem is that, in 2019, it is not raining cash anymore. And neither now nor then should precious national resources be spent in such a careless and callous fashion.

LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE

The Musharraf era old guard threatens the sustainability of the second round of HEC reforms from both within and without. The Planning Commission is wiser and would have been well-advised if it stays clear of this mockery of the project development and approvals process, in the same way the Chairman HEC and several federal secretaries have distanced themselves from it.

Should many of these so called “knowledge economy” projects — already submitted through improper channels or by strong-arming or arm-twisting of the bureaucracy — be approved, this would constitute a serious breach of the Rules of Business and a compromise of the independence of the Planning Commission.

It would also bring the country’s science and technology and higher education establishment back to where it all began when too much money pumped into ill-conceived projects resulted in corrupting and harmful consequences. It is true that science and technology and higher education need more, not less, investment in order to deliver. But more investment in things that do not address the most fundamental issues affecting impact and the focus on superficial outputs will not produce better results. It will only produce more bad results faster.

At the difficult economic juncture Pakistan finds itself today, this country can ill-afford to spend money on badly and hastily designed educational projects with no real strategy or strategic thinking in place. The higher education sector needs a clear strategy that is shared widely and debated and discussed before any real spending can be undertaken. But more importantly, it needs a different and more thoughtful approach that spends a little and evaluates impact before scaling.

The choice before the country’s leadership cannot be starker and clearer.

Dr Athar Osama is a former Member of the Planning Commission where he was responsible for S&T, ICT and Higher Education. He was a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum from 2013-2018 and a Fellow of World Technology Network. Athar holds a PhD in public policy specialising in Science and Innovation Policy.

0 Comments